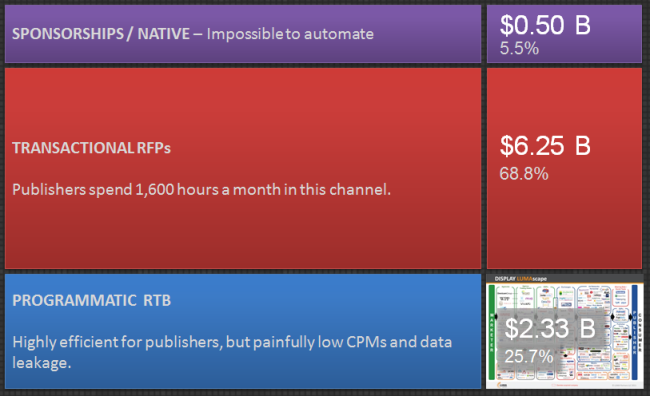

Nearly 70% of the $9 billion display media market still occurs in the “transactional RFP” channel. Source: Arkose Consulting

This post originally appeared in AdExchanger

Why Publishers Hate the Transactional RFP Business

I have been thinking about, and trying to solve, agency digital workflow problems since 2008.

Given the complexity of digital media, the variety of creative sizes, millions of ad-supported sites, and dozens of ad servers, analytics platforms, order management and billing tools, it goes without saying that the digital marketing stack has been hard for any agency to put together.

Recent research has tracked the immense level of complexity involved in digital media planning (more than 40 steps) and the tremendous expense involved in creating the actual plan (up to 12% of the media spend). It all adds up to a lot of manual work for which agencies are not willing to pay top dollar, along with frustrated agency employees, overbilled clients and a sea of technology “solution providers” that only seem to add to the complexity.

Media planning on the agency side is a big time suck. Yet some agencies are still getting paid for it, so it’s a problem that is going to get solved when the pressure from agency clients increases to the point of action, which I think we’re just now hitting in 2013.

But who is thinking about the publishers? Despite dozens of amazing supply-side technologies for optimizing programmatic RTB yield, there are only a few providers focused on optimizing the 70% of media dollars that flow through publishers’ transactional RFP channels.

DigiDay and programmatic direct software provider AdSlot and recently studied the transactional costs of RFPs. The sheer numbers stunned me. Here’s what one person can spend on a single RFP:

- 5.3 hours on pre-planning

- 4.2 hours on campaign planning

- 4.0 hours on flighting

- 5.3 hours on maintenance

- 3.3 hours post-campaign

That’s more than 22 hours – half a business week – spent creating a single proposal and starting a campaign, which, according to the study, has a less than 35% chance of getting bought and a staggering 25% chance of getting canceled for performance reasons after the campaign begins. The result is a 25% net average win rate. That’s a lot of work, especially when you consider how easy it is for agencies to lob RFP requests over the transom at publishers. On average, publishers spend 18% of revenue just responding to RFPs, which translates to 1,600 man-hours per month, according to the study.

So, we have a situation in which agencies, which are firmly in control of the inventory procurement process, are not only wasting their own time planning media, they are also sustaining a system in which their vendors are wasting numerous hours comporting with it. In short, agencies spray RFPs everywhere, and hungry publishers respond to most. The same six publishers make the plan every year, and a lot of publishers’ emails go unanswered. What a nightmare.

A Less-Than-Perfect Solution

To combat this absurdity, many publishers have placed large swaths of their mid-premium inventory in exchanges where they realize 10% of their value but avoid paying for 1,600 hours of work. The math isn’t hard if you know how agencies value your inventory. Publishers aren’t stupid. Inventory is their business, and most work very hard creating content to create those impressions. These days, every eyeball has a value. Biddable media has made price discovery somewhat transparent for most inventories. Programmatic RTB is great, but not all publisher inventories are created equal. A small, but highly valuable percentage will never find its way into an SSP.

Publishers will always want to control their premium inventories as long as they receive a greater margin after transactional RFP labor costs. Publishers who actually have strong category positioning, contextual relevance, high-value audience segments and a brand strong enough to offer advertisers a “halo” have to manage their transactional business so they can maintain control over who advertises and what they pay. This looks the year that demand- and supply-side software solutions may finally come together to solve the problem of “transactional RFP” workflow.

A couple of new developments:

- Demand-Side Procurement Systems Are Evolving: Facing significant pushback from clients and seeing new and accessible self-service media buying platforms gain share, agencies are looking hard at tools to gain efficiency. Incumbent software systems like Strata and MediaOcean are modernizing, while new, Web-based tools are gaining adoption among the middle market. Suddenly workflow efficiency is all the rage and agencies that spend 70% of their money in the transactional RFP space want a 100% solution.

- Supply-Side Direct Sales Systems Are Available: A few years ago, there were lots of networks and marketplaces for publishers to put inventory before going directly into exchanges. Many were more generous than today’s exchanges, but still offered low-digit CPMs and not much control over inventory. Now there are a variety of systems that plug directly into DFP and enable publisher sales teams to have real programmatic control over premium inventory. AdSlot, ShinyAds and iSocket are rapidly gaining adoption from publishers that want another premium channel to leverage, without giving up pricing control. To succeed, these publishers’ systems must be connected to the platforms that manage demand.

- Who Put Peanut Butter Into My Chocolate? What is slowly happening, and will continue in a huge way in 2014, is that demand- and supply-side workflow solutions will come together. What does that mean from a practical standpoint? Planning systems will be able to communicate with ad servers, eliminating double entry work; ad servers will be able to communicate with order management and billing systems, eliminating even more duplicative work; and the entire demand side system will be able to communicate orders directly into the publisher workflow systems and ad server.

Simply put: Agencies will be able to create a line item in a media plan, electronically transmit an order to a publisher, which the publisher will electronically accept, and the placement data will be transmitted into the publisher’s ad server. A line item will be planned, and it will begin running on the start date. Wow.

That’s what we are starting to call programmatic direct. It’s a world with a lot less Excel and email, with thousands of hours that won’t get wasted on transactional RFP workflow for agencies and publishers.

What kinds of amazing things can do with all that extra time?